Want to send me mail? Click here: tomrdavis@earthlink.net.

You can click on almost any image on this page to see a larger version.

We found a birding trip to Cuba led by Alvaro Jaramillo who regularly writes great columns in Birdwatcher's Digest and signed up for it. Here's a link to Alvaro's Adventures website.

Above is a map of Cuba showing the rough locations where we stayed. (1) Camagüey, (2) Cayo Coco, (3) Cienfuegos, (4) Playa Girón, (5) Las Terrazas, and (6) Havana.

There were 12 guests on the trip, two of whom are good friends of ours, and the co-leader of the trip was Arturo Kirkconnell, perhaps the world's top authority on Cuban birds and co-author of Field Guide to the Birds of Cuba. We planned to bird all across the island for 9 days of birding and one day in Havana to explore the city. The trip started in Camagüey and ended in Havana. Here is Arturo's website.

Almost everyone on the trip was a better birder than I am, and I'm less interested in birding than in bird photography: I'd rather get a good photo of birds at the price of occasionally missing a sighting. For most of the time I carried a large camera/lens/tripod combination, so I couldn't use my binoculars quickly: I had to set down the tripod which was usually on my shoulder before I could pick up the 'nocs. There is a description of my photography gear here.

The rest of this document is basically a trip report, arranged in the order in which we visited various places. I've included many photos of birds in the text, and usually the photos that appear are of birds that were seen at the associated sites (although the photos may be of the same bird, but taken at a different site).

Upon arrival in Cuba on November 30 Ellyn and I were interviewed at immigration separately, perhaps to make sure our stories matched, and the only delay was that they wanted to know our exact address while we were there. Even knowing the hotel name was not enough. Luckily, buried in our notes was the hotel name with the address. Altogether 7 of the 12 trip members arrived on the plane with us, a day early.

We had a nasty surprise when we picked up our luggage: Ellyn's lock and zipper had been completely torn off somewhere between Miami and Cuba. We don't know if it was an attempted theft or if the lock had somehow been caught in a mechanical mechanism and torn off there, and with not too much time available, it was hard to tell if anything was missing. It looked like almost everything was there with the exception of a water bottle, and that turned out later to be the case. We did know that we'd need to get another suitcase sometime, but we were able to use the old suitcase with all the stuff inside a pillowcase-sized bag. We were unable to report the problem to AA since there was no one in the office.

Cuba officially doesn't want to have anything to do with the US dollar, but it does have two kinds of currency: the regular peso (called a CUP) and a convertible peso (called a CUC). Cubans are paid in CUPs and tourists change their money for CUCs. A CUC, miraculously, is worth exactly one US dollar, no matter how the value of the dollar varies. A CUC can be converted to many (about 25) CUPs. There is a fixed charge for converting dollars to CUCs which is about 13 percent. At the end of a trip you can change back to dollars at a 1-1 ratio. A standard scam is that the 3 CUP note has a photo of Ernesto "Che" Guevara and is a popular souvenir from Cuba, so you're often offered the chance to change a 3 CUC note for a 3 CUP note to get your souvenir.

The 13 percent exchange rate only applied to US dollars. About 3 percent was the actual exchange fee, but there was an additional 10 percent tacked on for US currency. If you had to exchange a lot of money, the best strategy might be to convert the US cash into Euros or even Canadian dollars before making the trip to Cuba. Then you'd only be charged 3 percent.

It's apparently not too dangerous for Cubans to own US dollars nowadays, since most were happy to take US dollars as tips, et cetera. We did convert most of what we expected to spend into CUCs at the airport because we didn't know what the true situation would be when we arrived.

We stayed at Hostal El Paso and were told that the same people at the hotel owned the restaurant just up the street and we would get a discount if we ate there. It was a nice night, so four of us sat at a table outside the restaurant and had a nice meal. What we didn't realize was that there was another restaurant on the other side of the street and we had sat at their table. It was just as well: we'd get to eat at the El Paso's restaurant the next two nights.

Some of the group members were not happy with the El Paso restaurant's food: the fish was overcooked and the beef was tough. I ordered pork, figuring that that's what Cubans eat, so they'd probably get it right, and I was perfectly happy with my meal. I had no complaints about the hotel except that the hot water was basically just warm water.

On the right is Ellyn, sitting at the empty seat of a sculpture in Camagüey, talking to the other three women. The sculptress is Martha Petrona Jiménez who has a workshop across the street from this art installation.

On the right is Ellyn, sitting at the empty seat of a sculpture in Camagüey, talking to the other three women. The sculptress is Martha Petrona Jiménez who has a workshop across the street from this art installation.

December 1 was the official start of the trip and from then until the end, everything was paid for: meals, entry fees to parks, et cetera. We were told that we would pay for our alcoholic drinks, but since bottled water and beer were the same price, beer was often "free" and we usually only paid for stuff like wine and rum drinks.

By the way, ordering wine in Cuba is not always the best idea. The locals usually drink only beer and rum, so it's a good idea to stick with those. Since there's almost no market for wine, often any wine you can find has been sitting on a grocery shelf for who knows how long. At least a couple of the bottles that got opened had corks that were completely dry and disintegrated when their removal was attempted.

In fact, one evening when I and most of the rest of the group were out doing something else Ellyn noticed that at the reception of the El Paso were some bottles of wine. She was practicing her Spanish with the kid at the counter and learned that this was his first job and that he had only recently graduated from hotel school. She asked to buy a bottle of the wine, and the kid admitted that he had never in his life opened a bottle. Ellyn has had "some" experience with that, so she gave him a lesson.

The same kid commented on Ellyn's use of Spanish: that it was quite good. Ellyn said that it was because she was from California and that there are a lot of Spanish-speaking people there who can't speak English. The kid was amazed to learn that there were folks living in the United States who can't speak English.

Right: A statue of Ignacio Agramonte in Camagüey.

Right: A statue of Ignacio Agramonte in Camagüey.

The next day the final five trip members arrived on two different flights. During the day we wandered around Camagüey, taking some photos. Since we had the destroyed suitcase, Ellyn and I tried to buy almost no souvenirs since we weren't sure how we were going to get even our own stuff home.

Eleven of the twelve of us were from the United States and one from Canada, although the Canadian lives in Seattle. Two were good friends from home and altogether there were seven of us from the San Francisco Bay area, two from Chicago, two from Deleware and the one Canadian from Seattle. Almost all of them are better birders than I am, and all had done extensive travel all over the world, mostly in search of birds.

I have a theory that whenever there is a tour group with 12 or more people, one of them is guaranteed to be an asshole. The other 11 turned out to be great people, so I can only conclude one thing about myself ...

Statue of Christ at the top of a church. Note the lightning rod. Many of the churches installed lightning rods on the highest element, such as a cross or a statue, and hence many crosses and statues were damaged as a result.

Statue of Christ at the top of a church. Note the lightning rod. Many of the churches installed lightning rods on the highest element, such as a cross or a statue, and hence many crosses and statues were damaged as a result.

This trip made me wonder a lot about my color vision, especially in very low light. Time after time in low-light situations, someone would spot a bird and call out the species before even taking a look at it with binoculars. I'd find the bird, and even with my binos I couldn't see more than a silhouette. Even the Black-and-white Warbler, whose field marks make for the maximum contrast, I could sometimes see only a black bird. I'm glad I don't have to make a living as a bird guide.

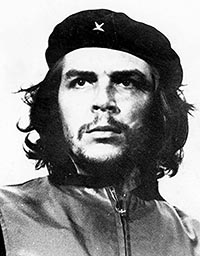

Left: Image of Ernesto (Che) Guevara on a building. One of the things that appeared all over the country were images of the heroes of the revolution. Che Guevara's image was by far the most common one, and most of the images were versions of the famous photo on the right. The Wikipedia article on Che Guevara says that this image by Alberto Korda might be the most famous photo in the world.

Left: Image of Ernesto (Che) Guevara on a building. One of the things that appeared all over the country were images of the heroes of the revolution. Che Guevara's image was by far the most common one, and most of the images were versions of the famous photo on the right. The Wikipedia article on Che Guevara says that this image by Alberto Korda might be the most famous photo in the world.

Guevara was born in Argentina and in Argentinian Spanish, the word "che" simply means something like "guy" or "buddy." Guevara used the word all the time, and eventually people started calling him by that name instead of Ernesto. When, after the revolution, he eventually became Cuba's minister of finance, he sign his name as "Che" and "Che" even appeared as a signature on the country's money.

The next nine days (December 2 through December 10) were almost all totally spent either birding or traveling to the next birding site. We did have a tour of the old city Trinidad, a visit to the museum in Playa Girón, and to the cave where Che Guevara was hidden with his troops during the Cuban missle crisis when there was a great fear of an invasion by the United States. At the end, we did spend a full day touring Havana, and the next day we returned to the US.

Left is the Cuban Palm Crow (Corvus minutus) which is endemic to Cuba. It is similar to the Cuban Crow, and the easiest way to tell them apart is by their call.

Left is the Cuban Palm Crow (Corvus minutus) which is endemic to Cuba. It is similar to the Cuban Crow, and the easiest way to tell them apart is by their call.

The birding days generally had the same structure: we got up quite early and we'd look for birds during the day. After getting settled back at the current hotel, we'd get together before dinner (usually about 7:00 pm or so) and go through the bird list, checking off all the species we'd seen.

Obviously not everyone saw every bird, and each person has his or her personal rule for what "counts" as a checkable bird. The most liberal people count every bird that anyone on the trip saw or heard which would have led to a list of about 160 bird species on this particular trip. Some count them if they heard the call, but most of those will mark the bird with some sort of "heard only" indication in the list.

On the right is the Cuban Pygmy Owl (Glaucidium siju), a Cuban endemic. We saw a few of these in many parts of the country. But the guides often used the owl's call to attract other birds. When a Pygmy Owl is around, other small birds gather around to scold it, as a warning to others that there is a predator present.

On the right is the Cuban Pygmy Owl (Glaucidium siju), a Cuban endemic. We saw a few of these in many parts of the country. But the guides often used the owl's call to attract other birds. When a Pygmy Owl is around, other small birds gather around to scold it, as a warning to others that there is a predator present.

Some count any bird that they saw, even if it was a quick glimpse of the bird in silhouette identified by someone else, and some only count birds where they got a good enough look to identify it themselves.

My personal rule is not to count heard-only birds since I'm not very good at the calls, and I only count birds that I got a good enough look at to identify them myself. Since I'm a shitty birder, I'm sure I had the shortest list count of anyone on the trip.

Fernandina's Flicker (Colaptes fernandinae). A Cuban Endemic.

Fernandina's Flicker (Colaptes fernandinae). A Cuban Endemic.

I'm actually way more interested in getting photos, so I often missed birds because it took time to get the tripod off my shoulder and set up before I could even get my binos to my eyes and often that was too late. This was a birding trip, not a bird photography trip, so I was happy to get what I got, and I tried to take photos after everyone had gotten a look at their bird.

On photography trips, or when Ellyn and I hire a private guide for birding, the situation is different and we see fewer birds, but maybe not that many fewer. On a birding trip, the second or later time you see a bird, not too much time is spent with it, so unless the view is great, there's not much time for a photo. Often if there was a chance at a much better shot, I'd stay behind and take photos, taking the chance that by not being with the group itself, I'd miss something, and this happened a few times.

For birders, one of the important things to try to do is to see as many endemics as possible. An endemic animal is one that can only be found in a particular place. I've attempted to indicate with its photo here which of the birds are Cuban endemics, like the Cuban Palm Crow, above, and the Cuban Pygmy Owl. Note that if the word "Cuban" appears as part of the name, that does not indicate that the bird is an endemic. It may mean that the bird was first identified in Cuba.

Giant Kingbird (Tyrannus cubensis). We only saw this bird at one site; at almost all the others we saw the more common Loggerhead Kingbird that looks similar.

Giant Kingbird (Tyrannus cubensis). We only saw this bird at one site; at almost all the others we saw the more common Loggerhead Kingbird that looks similar.

Barn Owl (Tyto alba furcata). According to our guides, this may be split into a new species, since it's different enough from the "usual" Barn Owl. This was a pretty lucky shot: I only had a couple of seconds to aim and shoot, and the owl was quite distant.

Barn Owl (Tyto alba furcata). According to our guides, this may be split into a new species, since it's different enough from the "usual" Barn Owl. This was a pretty lucky shot: I only had a couple of seconds to aim and shoot, and the owl was quite distant.

An interesting fact about the city of Camagüey is that originally it was on the coast, but due to many pirate raids, the city was moved significantly inland. Since moving the city made it possible to "do things right" the new version of the city was built with the most confusing possible set of roads so that invading pirates would have a hard time finding anything, and also have a hard time finding their way out.

Almost every block has the buildings constructed connected to each other, so it would be very difficult to get to the inner "courtyard" of any, and with all the doors locked, and defenders on the roofs, the situation for confused pirates would be even worse.

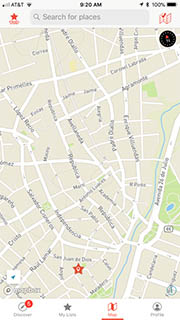

A phone app that I found very useful (and not only in Cuba) is called "City Maps to Go." If you're not sure you'll have wifi access, you can download the map for the region you're interested in (and not just cities: I downloaded the entire map of Cuba, for example) and then you can find your way around using the phone's GPS.

Here's a screen shot on the right from my phone of a part of the city of Camagüey, illustrating the chaotic arrangement of the streets. Of course you can plop down markers to show you where your hotel is, or your destination, et cetera.

I also used it on the long bus rides we took from one birding site to another, to know exactly where we were.

Cuban Tody (Todus multicolor). This is a Cuban endemic, and one of my favorites.

Red-legged Thrush (Turdus plumbeus rubripes).

Red-legged Thrush (Turdus plumbeus rubripes).

Another interesting thing I saw for the first time in paper, as opposed to on the internet, was copies of Granma, the official publication of the Cuban communist party. I noticed as I read the articles that the political slant was slightly different from that of Fox News.

Granma is the name of the yacht on which Fidel Castro, Ernesto Guevara, and others arrived in Cuba for the revolution. The online version is available here. Granma is also the name of a province of Cuba that took its name from Castro's yacht.

At least in the three issues that I looked at there was always included a story reminding viewers about the history of the revolution, even though it occurred almost 60 years ago.

Little Blue Heron (Egretta caerulea).

Little Blue Heron (Egretta caerulea).

We woke up early in Camagüey and drove to Cayo Coco, stopping to bird when something interesting was seen by somebody in the bus. Cayo Coco is on the north coast of Cuba, and it, and all along the northern coast had been hit hard by hurricane Irma about three months previous to our visit. ("Cayo" in Spanish means the same thing as "key" in English, as in the "Florida Keys.")

Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura). This is pretty much the same bird as we have at home, and throughout much of the Americas. What is a bit surprising is that the Black Vulture is very rare in Cuba, but it is quite common in Florida and Central America and in many of the islands surrounding Cuba. We saw hundreds of Turkey Vultures on the trip and not a single Black Vulture.

Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura). This is pretty much the same bird as we have at home, and throughout much of the Americas. What is a bit surprising is that the Black Vulture is very rare in Cuba, but it is quite common in Florida and Central America and in many of the islands surrounding Cuba. We saw hundreds of Turkey Vultures on the trip and not a single Black Vulture.

So because of Trump it became impossible to be just a tourist; we needed a reason to visit. At the time of this writing, there is a list of acceptable reasons to go to Cuba, and ours fit into the humanitarian/environmental category.

Cape May Warbler (Setophaga tigrini).

Cape May Warbler (Setophaga tigrini).

One of the main humanitarian/environmental purposes of the trip was to do bird surveys in the parts of Cuba that were hard hit by the recent hurricane Irma. Irma struck mostly the north coast of the island about three months before our visit. It was known that thousands of American Flamingos had been killed and in fact, only a tiny number were seen by us: far fewer than the number we would have expected six months earlier. Apparently flamingos have almost no defence in a big storm; they just wait it out and hope for the best. When we visited the southern coast of the island later in the trip there were thousands of them so it's likely that in future years the northern coast will be repopulated.

The bird that was most interesting, however, was the Cuban Gnatcatcher, a bird that is not only endemic to Cuba, but whose population is entirely in the mangrove swamps on the north coast. Before the hurricane it was generally easy to find: you'd hear it regularly and you'd probably see eight or ten individuals on any birding outing there.

Royal Tern (Thalasseus maximus).

Royal Tern (Thalasseus maximus).

We were in gnatcatcher territory for three days and tried at many likely sites, and not only did we not see any, but we did not hear any, either. I hope that a few survived, but the species sure got hammered by Irma.

Lesser Yellowlegs (Tringa flavipes).

Lesser Yellowlegs (Tringa flavipes).

The place we stayed for two nights in Cayo Coco looked very impressive, and was one of the few places on the north coast that were still open for business after hurricane Irma. Many of the other resorts were still missing their roof, or were otherwise badly damaged.

The resort is obviously aimed only at foreign tourists, and there were plenty of them. It had beautiful pools, great food, waiters to serve you anything you wanted, free classes all day long for anything from yoga to Spanish lessons, et cetera. It would have been the perfect place for us to stay except that our toilet didn't work and there was no hot water. There wasn't much we could do about the hot water, but there was a large decorative bowl in our room that could be filled with water from the tap and poured into the toilet bowl to flush it.

Cuban Black-Hawk (Buteogallus gundlachii). A Cuban endemic.

Cuban Black-Hawk (Buteogallus gundlachii). A Cuban endemic.

Zapata Sparrow (Torreornis inexpectata varonai). A Cuban endemic.

Zapata Sparrow (Torreornis inexpectata varonai). A Cuban endemic.

Speaking of Spanish lessons, I found the Cuban version of the language very difficult to understand. But every Cuban seemed to be able to speak a more "standard" version, if necessary. I could carry on conversations with anybody, and understand almost every word, but when Cubans were talking to Cubans, it was very hard. It wasn't simply the fact that native Spanish speakers were hard to understand: our trip leader Alvaro is from Chile and the Cuban guide Arturo was from Cuba and when they spoke Spanish together, I could understand almost everything. But when Arturo talked to other Cubans, the conversation was a complete mystery.

Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus). This is just like the ones from home, but who could resist taking this photo with such perfect light?

Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus). This is just like the ones from home, but who could resist taking this photo with such perfect light?

West Indian Whistling-Duck (Dendrocygna arborea).

West Indian Whistling-Duck (Dendrocygna arborea).

Here is a random photo that's representative of most of the mangroves we saw on the northern shore of Cuba. Note that a lot of the trees aren't perpendicular to the ground.

Here is a random photo that's representative of most of the mangroves we saw on the northern shore of Cuba. Note that a lot of the trees aren't perpendicular to the ground.

Hurricane Irma sure did a number on the north coast.

La Sagra's Flycatcher (Myiarchus sagrae).

La Sagra's Flycatcher (Myiarchus sagrae).

Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus).

Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus).

There was a Merlin nearby, so this flock of stilts got freaked out over and over again. Each time, they'd fly around in a closely-packed group for two or three trips around the lake. Then they'd settle down and wait for a few seconds before freaking out again. Here's a typical freak-out session.

Cuban Bullfinch (Melopyrrha nigra nigra).

Cuban Bullfinch (Melopyrrha nigra nigra).

Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos).

Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos).

Oriente Warbler (Teretistris fornsi). A Cuban endemic.

Oriente Warbler (Teretistris fornsi). A Cuban endemic.

Reddish Egret (Egretta rufescens).

Reddish Egret (Egretta rufescens).

It would be nice to have taken a video of this psychopath. Rather than sneaking up on its prey and taking it with one stab, this guy races around like a lunatic, stopping every so often to spread its wings to shade the water from the sun, and presumably allows it to get a better view of the fish underneath.

Smooth-billed Ani (Crotophaga ani).

Smooth-billed Ani (Crotophaga ani).

There were a lot of horse-and-buggy combinations on the streets, both in the cities and out in the country. Of course there were no autos manufactured in the United States after 1959 (the year of the Cuban revolution), but there were some Russian cars and tractors. Here's a photo of Alvaro leaning against a Russian Lada, that was miraculously still working.

In Havana, and to a lesser degree in other parts of the country, there were old US cars that are still running. See the section below on Havana for some photos of those vehicles.

Since 1959 it has been impossible to obtain parts for US cars, so the ones that are still in working condition appear to be in good shape on the outside, but under the hood they are almost all Frankenstein monsters, with Hundai engines, or diesel engines from Russian tractors, or who knows what. Most of the nicest looking ones in Havana were used as taxis for tourists like ourselves.

Blue-headed Quail-Dove (Starnoenus cyanocephala). A Cuban endemic.

Blue-headed Quail-Dove (Starnoenus cyanocephala). A Cuban endemic.

Bee Hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae). A Cuban endemic and also the smallest bird in the world.

This was another reason we wanted to visit Cuba: to see the smallest bird in the world. It turns out that a guy noticed that a bunch of these birds were feeding in one of the trees in his backyard, so he has been modifying the plants in his yard to make it more and more attractive to the Bee Hummingbird. As a side effect, it's more and more attractive to other birds as well, and not just this hummer.

This was another reason we wanted to visit Cuba: to see the smallest bird in the world. It turns out that a guy noticed that a bunch of these birds were feeding in one of the trees in his backyard, so he has been modifying the plants in his yard to make it more and more attractive to the Bee Hummingbird. As a side effect, it's more and more attractive to other birds as well, and not just this hummer.

Another side effect is that lots of birding groups stop by for an almost certain sighting of this bird, and usually a good percentage of them leave tips. We surely did!

He had a video of the inside of his house during the recent hurricane Irma where he captured a number of these tiny birds and kept them and fed them in a giant enclosure in his house until the hurricane had passed through.

Here's a photo of me with the owner of the Bee Hummingbird house.

Cuban Emerald (Clorostilbon ricordii).

Yellow (Golden) Warbler (Setophaga petechia gundlachi).

Yellow (Golden) Warbler (Setophaga petechia gundlachi).

Summer Tanager (Piranga rubra).

Summer Tanager (Piranga rubra).

I got this photo at the Bee Hummingbird guy's house.

Cuban Green Woodpecker (Xiphidiopicus percussus). A Cuban Endemic.

Gray Catbird (Dumetella carolinensis).

Gray Catbird (Dumetella carolinensis).

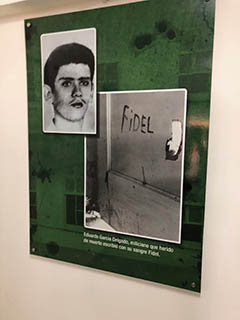

On the left is a photo of one the heroes, Eduardo Garcia Delgado, who was mortally wounded, but wrote the name "Fidel" with his own blood. That inscription can be seen on the lower right photo on the image on the right being carried during a march.

On the left is a photo of one the heroes, Eduardo Garcia Delgado, who was mortally wounded, but wrote the name "Fidel" with his own blood. That inscription can be seen on the lower right photo on the image on the right being carried during a march.

The photos above are of just a random selection of the museum exhibits.

We saw hundreds of these on the southern coast, and almost zero in the hurricane-ravaged north.

Gray-fronted Quail-Dove (Geotryon caniceps). A Cuban endemic.

Gray-fronted Quail-Dove (Geotryon caniceps). A Cuban endemic.

Zenaida Dove (Zenaida aurita).

Zenaida Dove (Zenaida aurita).

Bare-legged Owl (Margarobyas lawrencii). A Cuba Endemic. It's peeking out of a hollowed out tree, so we really should only check off half of this bird.

Bare-legged Owl (Margarobyas lawrencii). A Cuba Endemic. It's peeking out of a hollowed out tree, so we really should only check off half of this bird.

Northern Waterthrush (Parkesia noveboracensis).

Northern Waterthrush (Parkesia noveboracensis).

Cuban Parrot (Amazona leucocephala leucocephala).

Cuban Parrot (Amazona leucocephala leucocephala).

Great Lizard Cuckoo (Coccyzus merlini).

Great Lizard Cuckoo (Coccyzus merlini).

Zapata Wren (Ferminia cerverai). A Cuban endemic.

Zapata Wren (Ferminia cerverai). A Cuban endemic.

We did find the wren, but due to unlucky seats on the boat, a couple of us got only shitty views. I got this snapshot which is good for an identification shot, but I doubt that it'll make the cover of National Geographic.

Common Yellowthroat (Geothlypis trichas).

Common Yellowthroat (Geothlypis trichas).

Cuban Trogon (Priotelus temnurus). A Cuban endemic and also the national bird. Note the spectacular shape of the tail feathers. It also boasts the colors of the Cuban flag.

West Indian Woodpecker (Melanerpes superciliari superciliari).

Green Heron (Butorides virescens).

Green Heron (Butorides virescens).

Stygian Owl (Asio stygius siguapa).

Stygian Owl (Asio stygius siguapa).

We had basically finished birding for the day, but there was a possibility that we'd go out that evening "owling." But first we went to a restaurant, ordered dinner and drinks, and just about when the drinks arrived, Alvaro got a "birding 911 call" that a Stygian Owl had been spotted about 10 minutes away from the restaurant.

So we piled out of the restaurant and onto the bus and raced to the place where the owl had been spotted. He (she?) was way up in a tree, in the middle of town, and lots of folks were looking. It was very dark, and the only way to get a good view was when a flashlight was shined on the owl. I managed to brace my camera against something and took a lot of shots, a few of which turned out. This is the best, with the owl looking up, presumably to search for insects. It never looked directly at us, at least when there was a light on it.

After spending about 10 minutes with the owl, we returned to the restaurant and had a great meal. It must have convinced the owners of the restaurant that all birders are totally insane.

Here are a couple of photos of the American Kestrel. We saw them basically every day multiple times while riding on the bus, sitting on telephone wires.

Cuban Pewee (Contopus caribaeus caribaeus).

Cuban Pewee (Contopus caribaeus caribaeus).

Loggerhead Kingbird (Tyrannus caudifasciatus). The photo on the right is just the head portion of the photo on the left.

The three images above are of the cave where Che Guevara and his men were hidden during the Cuban missle crisis. They feared an invasion from the United States. The building where Che stayed is visible in the leftmost photo.

Obviously the surroundings have been spiffed up quite a bit for modern visitors.

Cuban Solitaire (Myadestes elisabeth). A Cuban endemic.

Cuban Solitaire (Myadestes elisabeth). A Cuban endemic.

This was Ellyn's favorite bird in Cuba, not necessarily for its looks, but for its song. It certainly had a distinctive song, but I don't rank it with the best. Ellyn had Arturo sign our "Birds of Cuba" field guide on the plate of the Solitare.

I got one chance at a photo, and was really lucky to do as well as I did.

Cuban Grassquit (Tiaris canorus). A Cuban endemic.

Yellow-faced Grassquit (Tiaris olivaceus).

Here is a photo of some of us in a 1957 Plymouth (I think) and a view of three other classic cars in the background.

Here is a photo of some of us in a 1957 Plymouth (I think) and a view of three other classic cars in the background.

Below is a video I took from the front seat of the car as we drove from the hotel into old-town Havana.

The first stop was at the Plaza de la Revolución which is surrounded by some of the main governmental buildings in Havana..

Here is Ellyn with me in front of a building in the main square with another image of Che Guevara in the background.

Here is Ellyn with me in front of a building in the main square with another image of Che Guevara in the background.

This is the original Bodeguita del Medio: one the the places where Hemmingway hung out.

This is the original Bodeguita del Medio: one the the places where Hemmingway hung out.

We saw similarly-named places in other cities in Cuba, and in fact, there is a Cuban restaurant near home in the city of Palo Alto, with the same name.

Here is Ellyn in front of the Hotel Presidente.

Here is Ellyn in front of the Hotel Presidente.

Ellyn's great uncle Arthur owned this hotel before the Cuban revolution, and in 1959 her cousin was married and planned to spend his honeymoon in great uncle Arthur's hotel. But on the plane ride to Cuba the captain announced that a revolution was occurring, and that it was impossible to land in Havana, so the plane continued on to Jamaica. That's where the cousins spent their honeymoon.

The hotel, of course, was seized by the revolutionaries and poor uncle Arthur lost the property.

Ellyn decided to get a photo of the hotel to send to her cousins, and here it is.

Mangrove Buckeye (Junonia genoveva).

Mangrove Buckeye (Junonia genoveva).

Seaside Dragonet (Erythrodiplax berenice (?)).

Seaside Dragonet (Erythrodiplax berenice (?)).

Northern Curly-tailed Lizard (Leiocephalus carinatus (?)).

Northern Curly-tailed Lizard (Leiocephalus carinatus (?)).

Cuban Tarantula Hawk (Pepsis sp?). The guide called this a "Tarantula Hawk" and I couldn't make an exact identification of the species using Google. It was interesting to read about why you should not get stung by one. Read the section called "The Sting" here.

Cuban Tarantula Hawk (Pepsis sp?). The guide called this a "Tarantula Hawk" and I couldn't make an exact identification of the species using Google. It was interesting to read about why you should not get stung by one. Read the section called "The Sting" here.

Red Saddlebags (Tramea onusta (?)).

Red Saddlebags (Tramea onusta (?)).

It was usually mounted on a moderate-weight Gitzo tripod with carbon fiber legs and using the Really Right Stuff ball head.

The image stabilization (called "Vibration Reduction," or "VR" by Nikon) is pretty good, and if there was no time to set up with the tripod, hand-held shots turned out to be pretty good. I shot most of the time with shutter priority, setting the shutter speed to 1/250 of a second or more if it was hand-held, and often much lower if the bird was not moving much and I had a tripod to support it. I took some photos of perching birds at as low as 1/10 of a second so as to use lower ISO numbers and obtain finer grained shots.

When the light was low the camera basically always chose the f/8 aperture, and I used the "ISO Auto" setting so that the camera would jack up the ISO to get the right exposure at the expense of a grainier result. One thing the Nikon D5 does well is to take photos with high ISO settings that are not too bad. The D5 will go up to about ISO 100,000. The photo of the Stygian Owl on December 8 was probably shot at ISO 50,000 or so, since the owl was far away, it was pitch dark, and all the available like came from a hand-held flashlight.

I foolishly took along another lens: the 24-120 mm f/4 that I thought I'd use for non-bird photos, but it never got out the the camera bag. We had a little Nikon V1 point-and-shoot that Ellyn almost always carried and the camera on the iPhone that I had also was just fine for most non-bird photos. I did take along an older Nikon D4 body just in case there was a camera failure, but the D5 worked fine for the whole trip, so the D4 was never used at all. I think that next time the only major change I'll make is to omit the 24-120 mm lens.

Return to my home page for more links to photos

Tom Davis ( tomrdavis@earthlink.net)